Fluidity cannot live without strength, nor grace without pressure.

Fluidity cannot live without strength, nor grace without pressure.

As the opening of the exhibition approaches, we invited Los-Angeles based artist David-Simon Dayan to talk about his upcoming photography exhibition Ballerino, which will be held in A Love Bizarre (a queer focused gallery space) in Los Angeles once the lockdown ban has been lifted.

How has your time in isolation been?

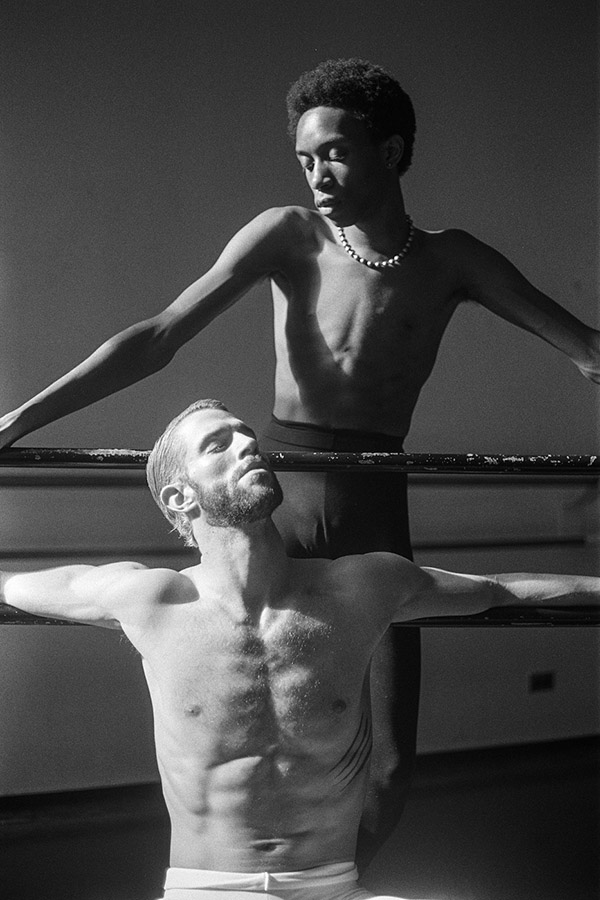

It’s been mostly positive. Of course there are challenges; not having work for such a long period is difficult, shoots and the show being postponed, but I’m enjoying the chance to relax and reflect. Many people seem to be focusing on things they might have previously neglected, which is reason to be grateful. I’ve been spending more time in nature than ever before, so that’s literally a breath of fresh air.

What do you see in front of you at the moment?

Right now, I’m sat at a desk in front of this beautiful window in the countryside. I’m in the South of England, looking out at a field to my left, a forest of mostly birch and oak trees to my right. There’s a wooden gate that runs along the perimeter of it. The other day a group of stags found themselves on this side of the fence, which was exhilarating to witness; their considerable, muscular bodies paired with an ability to run and jump with unbelievable grace. Sounds familiar now, doesn’t it?

Have you been taking many photos?

I’ve shot some self-portraits, and I’ve taken some of the land, but I haven’t felt as inspired as I do when I’m around a shimmering group of people in the city. It’s been more of an opportunity to write, something I’ve been putting off because of those excuses that are so easy to find when everything else is going on. And I’ve been eating books up. Just an insatiable literary pig.

Anything good?

Yes and no. I’ve just finished Vidal’s City and the Pillar, which I’m well aware I’m late to, but it was a fascinating peek into the push and pull of self-acceptance. And I just read Isherwood’s A Single Man, which was a brilliant portrayal of the complexities of grief, friendship, and love. Now I’m reading a a couple things side by side; Foer’s We are the Weather, which is this heartfelt prose about climate change and the reasons why humankind struggles to believe it and make the necessary adjustments. Bleak, but educational, and he employs both storytelling and science to inform the reader. And a novel called Swimming in the Dark, which is about a young man experiencing his first love in Poland under the oppressive law of the Security Service. It’s equal parts romance and fear. The narrator, as a child, knocks on the door of his first crush and gets threatened by the new inhabitants not to come looking for “the Jews,” which feels extremely close to home, knowing that my grandmother was part of one of these Jewish families forced to flee the country.

Do you remember the first objects you became interested in taking pictures of?

First, it was things around the house as a child, then it became friends, nature, lovers. I’ve always felt pulled to photograph people. Portraits are what interest me, portraits of the members of certain aspects of society. Beauty plays its role, of course, when you’re shooting for fashion specifically, but beauty is unique to the viewer, and there’s much more to that then physicality. Context is important, as is the spirit, or essence.

And when did you decide to shoot on film?

It was shortly after I moved away from home and into New York. I had been shooting on a digital camera as hobby, but I wanted something that felt more real, something that required patience and understanding. On a digital camera, one can easily shoot thousands of photos of the same thing without much thought, it is ridiculously indulgent. With film, not only do you consider more before actually clicking, but it’s more of an act of presence. Plus, we’re all in a constant battle with our relationships to technology, aren’t we? With film, there isn’t another screen in front of your face.

Your work has en element of eroticism, does it not?

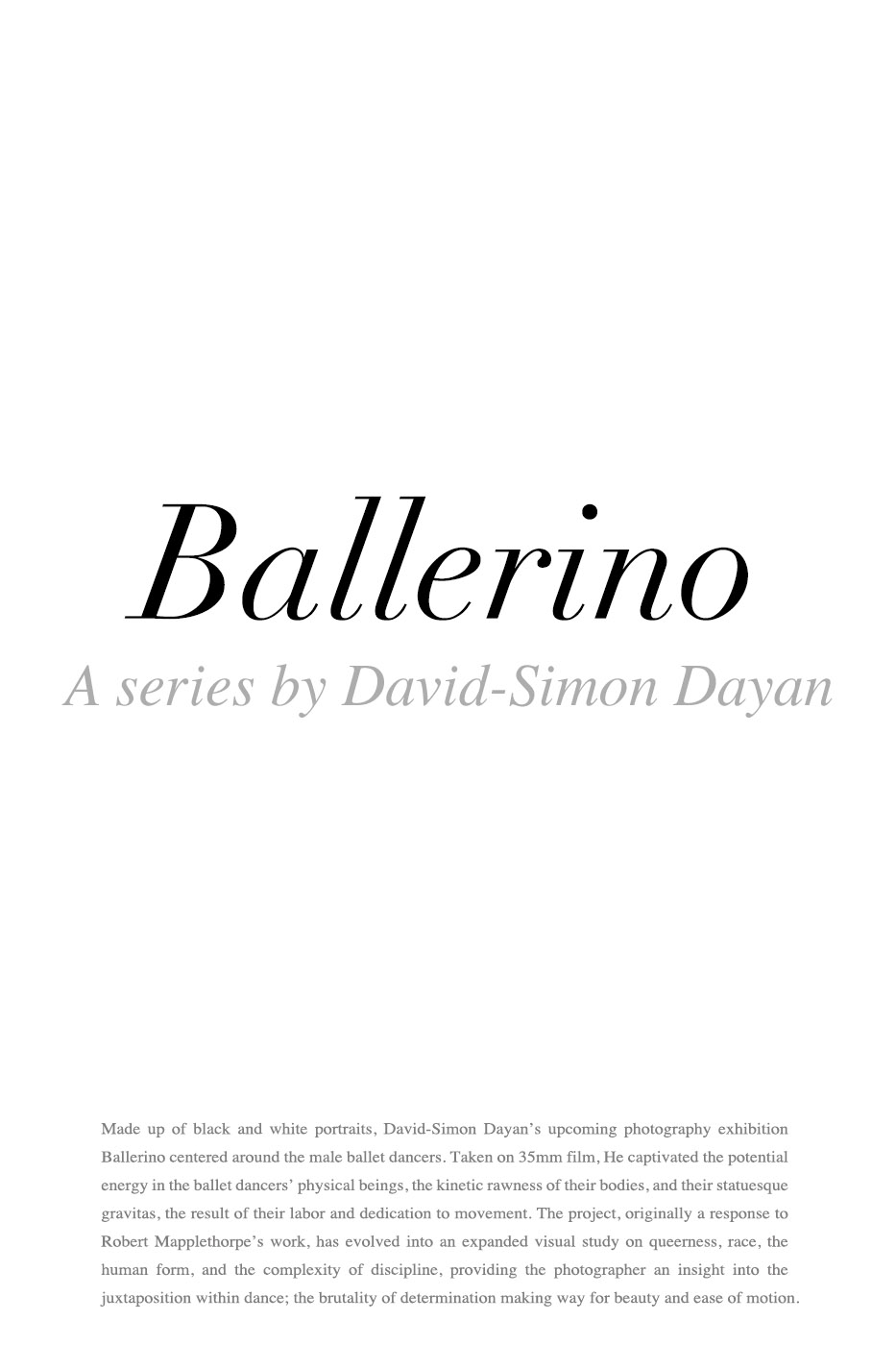

While the human form can be seen as erotic, and quite a bit of my work carries an element of that, I believe this shifts, speaking to the the dialogue between subject, artist, and viewer. Photographing nudity is important, with the hopes of liberation and transcendence. With dancers, there’s a natural eroticism to witnessing the extraordinary results of labor in their bodies, surely, An attraction to this strength is instinctual. The fibers of their muscles and tendons, the bare skin paired with the raw grain of films, yes, eroticism is definitely present, but we all experience eroticism uniquely. It’s based on the viewer’s own experience. In my series Veil, this was a conscious attempt, a tool of exploration, a commentary on sexual objectification and the male form. With Ballerino, any eroticism or homoeroticism present may be blatant to one yet invisible to another.

Your work often concentrates on the human form. What is your favorite part of the body?

Every body is unique, no? So with every subject, this changes. But my focus on the human form may not be entirely conscious, it’s solely what inspires me to shoot. I have yet to feel the same way about, say, a landscape thus far. Maybe that will change, but when you shoot portraits, every subject has their unique look, their unique way of being, so witnessing, interacting, and creating together is the aim.

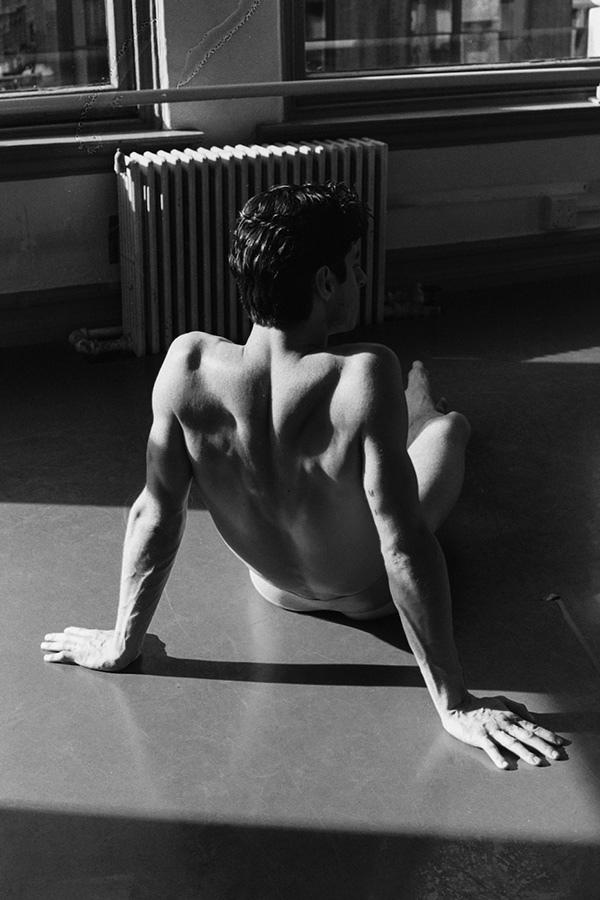

Let’s talk about your first solo show, Ballerino. What inspired this series?

Originally, it was the meeting of a few things. I was living in New York at the time, and had some friends that danced ballet, which is a craft I have the utmost respect for. Dance has always been something I’ve loved, but the people that dedicate their days to it, the discipline involved, it’s extraordinary. At the time, I was first learning about Mapplethorpe, and felt moved by his work, by not only what he was making but the stories behind it, and I felt this pull to pay him respect by shooting a loose homage to his work

What was it like working with some of these dancers who are highly regarded in the world of ballet?

They have all carried with them such an ease. Dancers have relationships with their bodies most don’t. We walk around and we see, in ourselves and in others, broken bodies everywhere. Dancers can carry themselves, their instruments, in a way that captivates a room, that tells a story. James Whiteside, for example, inspires countless aspiring dancers, and I have the utmost respect for him. We’ve shot together a couple times now, and I’m grateful to have had the experiences. His warmth is palpable, and his silliness is contagious.

And you mentioned the opening had to be pushed. How does that feel?

Safety is more important than anything else that’s being missed out on. I’m not the only one. People are losing their jobs and lives. It’s frustrating, surely, but it will pass, and maybe people will shift the way they live, maybe we’ll all become a little more conscious. I do hope that this ends soon, with as little life lost, and we can all continue to move forward with newfound perspective. And that Americans don’t forget how poorly this has been handled when it comes time to vote.

Do you know when the show eventually take place?

I don’t, unfortunately. While art is essential in many regards, which we can see by the mass amounts of it being consumed by those in isolation, it is not essential in the way hospitals or markets are right now. We turn to art in the face of adversity, but nobody wants to put people at risk, so we’ll adapt. We’re considering the possibility of an online show, and there’s a chance the gallery will be creating some sort of print publication that’s more accessible. Time will tell.

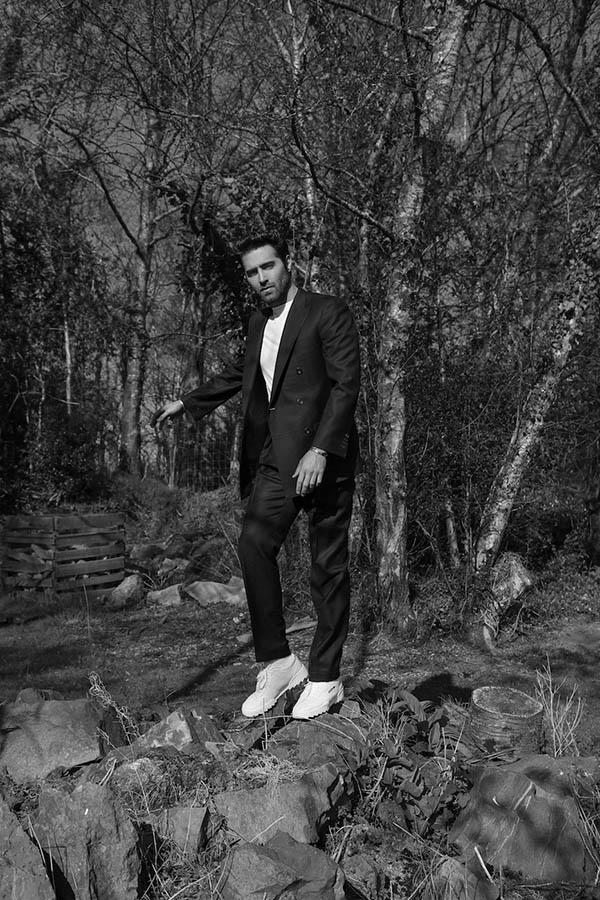

David-Simon Dayan is a twenty-four year-old artist based in Los Angeles whose work often explores the male form and queer community. As a regular contributor, his photographs and poetry have appeared in Cap74024 and at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

You can visit his instagram (@sirdavidsimon) and website for more of his works.