Photographs of the eccentrics.

Forty-five years after the death of Diane Arbus, perhaps the most controversial among the American photographs of the twentieth century, broke out a sort of Arbus mania in the United States. Thanks to the recent publication of the biography, and especially an exhibition that the new Met Breuer dedicated to the artist with works that have never seen before.

Amy and Doon, daughters and heirs of the immense heritage of Arbus, a few years ago have donated the archive of the photographer to Metropolitan Museum.

Only recently the staff of the Met, which has established a true Diane Arbus Archive, has realized the immensity of that heritage. An unspeakable amount of films (about 7,500), hundreds of meters of negatives never watched, and also diaries, letters, unpublished documents that will be available to be seen by anyone in a few years. For decades, the daughters have been revealing some pieces for each event that was dedicated to the memory of their mother. They have not authorized any biography and were taking care for not to disseminate photographs anyhow except for the exhibitions or monographic books. The first, Amy, is a famous street photographer and teacher at the International Center of Photography. The second, Doon, after it has been for years the personal assistant of Richard Avedon, today dedicates her heart and soul to the real estate of the mother.

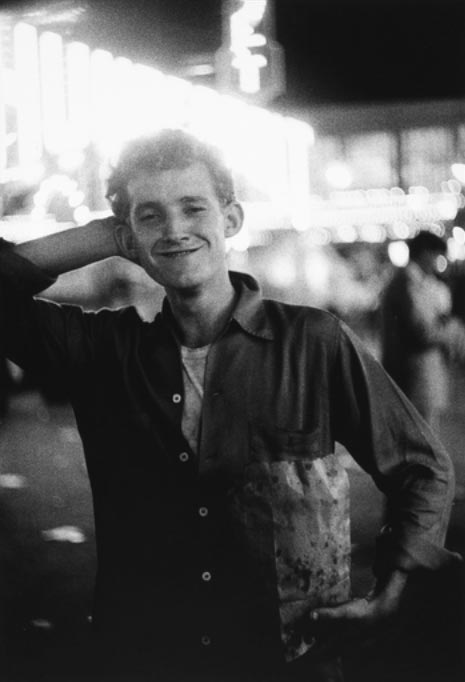

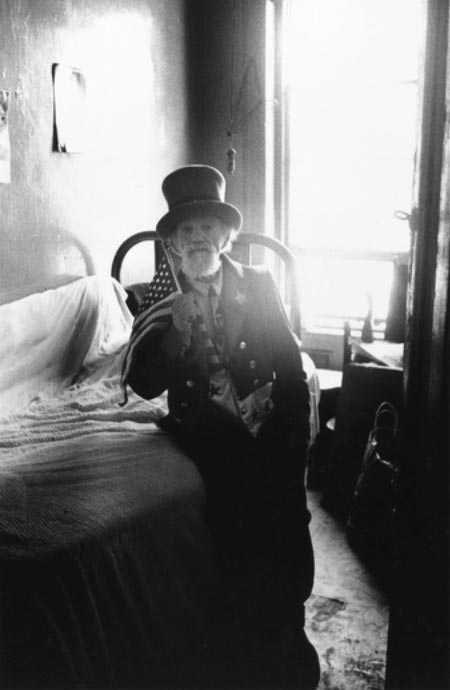

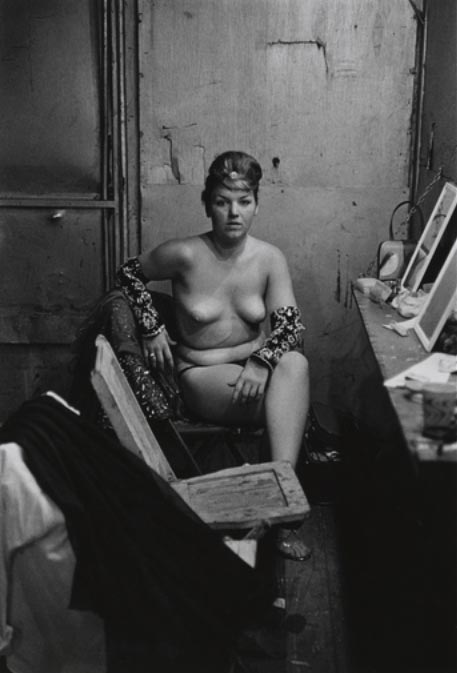

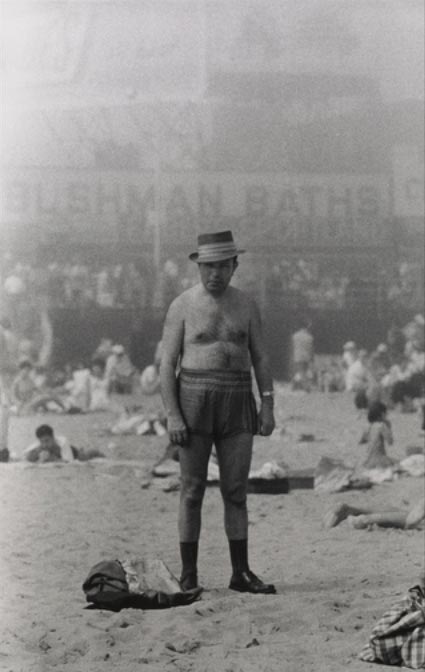

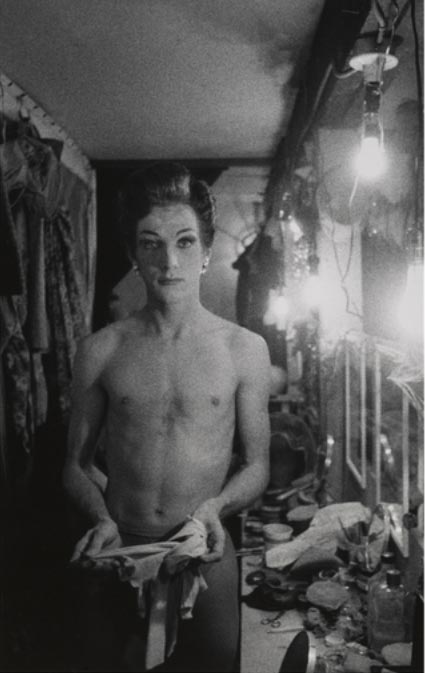

Diane, pronounced dì-an, not dà-ian – photographer insisted that the name was said correctly – was the first to photograph the so-called eccentrics. Transvestites, nudists, jugglers, people suffering from mental and physical problems, prostitutes, giants and dwarfs. Anyone who had a bit of eccentricity became a subject to be immortalized in her bizarre photo album. But it was, first of all, herself, a complex personality, almost impossible to decipher.

“Everything that happened seemed mysterious, decisive and unimaginable, naturally not for her. And this happens only to a genius”, once said Richard Avedon, a close friend of the photographer as well as Stanley Kubrick, that was inspired by her for the creepy twins in his famous “Shining”. Patti Smith in “Just Kids” wrote Diane was always around the Chelsea Hotel constantly looking for the subjects to photograph with a restless expression, like if the endl of the world was very close by.

So she started to wander around New York with a huge camera on her neck and when she was ready she knocked on the door of one of the biggest photographers of the epoch – Lisette Model. The two became friends. It was Model to say a sentence that was fundamental for Diane and worked better than any other learning. “The more specific you are, the more universal you’ll be”.

Those are the years Diane became “Arbus”, the myth and the legend, as we said. The one that who was able to get where no one else has ever been before. The “photographs of the freaks”, as she is now recognized and that’s a definition that she considered unjust, since she saw no freaks in her photographs, but herself. Even about the triplets photographed in New Jersey in 1966, she said, “they remind me of myself.”

She moved in a small house in Charles Street (that is for sale today to a record of twelve million of dollars and the first characteristic on the announcement is that she lived there), after getting her little daughter to bed, she ventured alone in the city nights accompanied by his inseparable camera. She walked around Times Square, at the times a scenario of gangsters and prostitutes, till the first rays of light. Sometimes she went up to the unfamous Lower East Side, returned in the lodge of the West Village, and, as if nothing had happened, came home to make eggs for the girls. She constantly works with two Mamiya cameras, flashes, sometimes a Rollei, a tripod, each type of lenses she had, a light meter and lots of packages with film. The Rolleifles was the camera she used the most. It was a relatively small and compact camera with the viewfinder placed on top of it. The image that Diane perceived at the time of shooting was reversed but the fact of not having filters between herself and the subject and not having to hide her face gave her the advantage of being able to communicate with them. “I don’t press the shutter”, she wrote in a letter in 1960. “The image does. And it’s like being gently clobbered.”

In a rare video interview, one year after Diane’s death, Doon Arbus has defined better than anyone what was the photography for his mother. “For her, the photography was a secret. I mean, not the process or the fact that she was a photographer, because she loved to tell us what she did, where she had gone, who photographed. But something about what was happening during her shootings, that was a secret. It has something to do with the way she grow up. In her family there was a great sense of what was or was not prohibited, and photograph for her was a way to break those prohibitions”.

In the afterword to “Revelations”, the immense catalog that Random House printed in 2003 in support of an exhibition organized in collaboration with the San Francisco MoMa, Doon wrote that the photographs of his mother “are eloquent enough not to require explanations, instructions, books on how to interpret or biographies to support them.” In the 60’s the kind of photography that Diane Arbus invented, and that today could be defined between the intimate and the introspective, wasn’t popular as today. There was the photojournalism and fashion photography, or in generale an advertising’s style of photos. That kind of portraits were just for commission. At her first exhibition at the MoMa in 1965, Yeu-bun Yee, a young librarian of the museum, was commissioned to clean every morning the glass surfaces of her photographs, daily covered of spitting.

She committed suicide in July 1971. Before her death, she wrote a note to her friend and teacher Lisette Model. It’s a postcard that was put in the mailbox and there was written simply “be happy”.

“A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.” she wrote on her diary and that’s why the secret of her art cannot be understood at all. One of Diane close friend, Pati Hill, once complained with her. “I’ve always said everything about me and you’re still full of secrets.” she said. “I need my secrets,” Diane replied. And forty-five years after her death, and after hundreds of published photos, she is still full of secrets. Perhaps her most successful masterpiece is that.

Text: Maurizio Fiorino

Translation: Irene Belous

The first biography of Arbus went out years ago and was published in Italy by Feltrinelli. Patricia Bosworth, the journalist that wrote it and did a scrupulous job interviewing everybody connected to Arbus, was accused by the daughters of having given too much importance to private facts of the photographer’s life and not talking about the pictures, that made this book more of a gossip publication rather than a real biography.

A new biography just came out written by Arthur Lubow, journalist for the New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker and Vanity Fair. The ten years of work titled simply “Diane Arbus – Portrait of a photographer” is a 750 pages where the existence of the photographer is sectioned from year to year and comes out to be the portrait of a complicated woman who probably will never be understood completely.

Since childhood Diane Nemerov appears restless. The second of three children, daughter of jewish parents from the classical American middle-upper class – her family was the owner of large stores Russek’s, a sort of shopping center famous for his furs and leather gloves – Diane had a childhood that was similar to all the rich girls of the time. Lived in the apartments at Park Avenue and Central Park West, with a personal nanny, butlers, luxury.

At the age of 13 Diane fell in love with a Russek’s young employee, 18 years old. His name was Allan Arbus, who had a dream to become an actor, but shared the interest of his young wife – photography. After taking part in the war in Myanman he acquired a considerable experience as an army photographer, Allan back to New York and together with the young wife decided to open a photo studio. Him behind the camera, her as stylist.

They worked in fashion photography for various magazines, but at the end of 50’s something went wrong. Allan wanted to break into Hollywood while Diane was overwhelmed. “I hate the fashion photography because the clothes do not belong to the people who wear them. When the outfit belongs to someone it takes the characteristics and defects of the person, and that’s perfect,” she noted in his diary.

Her approach to the subject was delicate, as Lubow explains. Some of them were interviewed in new biography. Diane gave attention to her subjects – the attention that they not received by anyone, and so many of them were very flattered. She discovered them on the street or at the train stations. After she met them, she needed months, sometime years, before she took her first picture. Giants, dwarfs, transvestites – they all became part of her family. Diane listened to their stories, she wanted to know everything before to take the first picture. She defined freaks aristocrats, because, she wrote in a note, they were “born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life.”

What happened during all her photo sessions is unknown, and remains the secret of Arbus that everybody wants to investigate and that the daughters jealously maintain. It is well known that Diane liked to seduce her subjects. The giant tells that he was proposed with a lot of boldness, and he thought that it was strange – he was 3 times bigger than her. She also had regular lovers. She had a close relationship with her brother, the famous poet Howard Nemerov, for her entire life. They slept together until a few weeks before her death. Not only she has photographed orges, but was a part of it. She had a sexual relationship with Gay Talese and the writer of the beat generation, Norman Mailer, after posing for her, was so upset that he said “giving a camera to Diane Arbus is like a giving a hand grenade to a baby.”