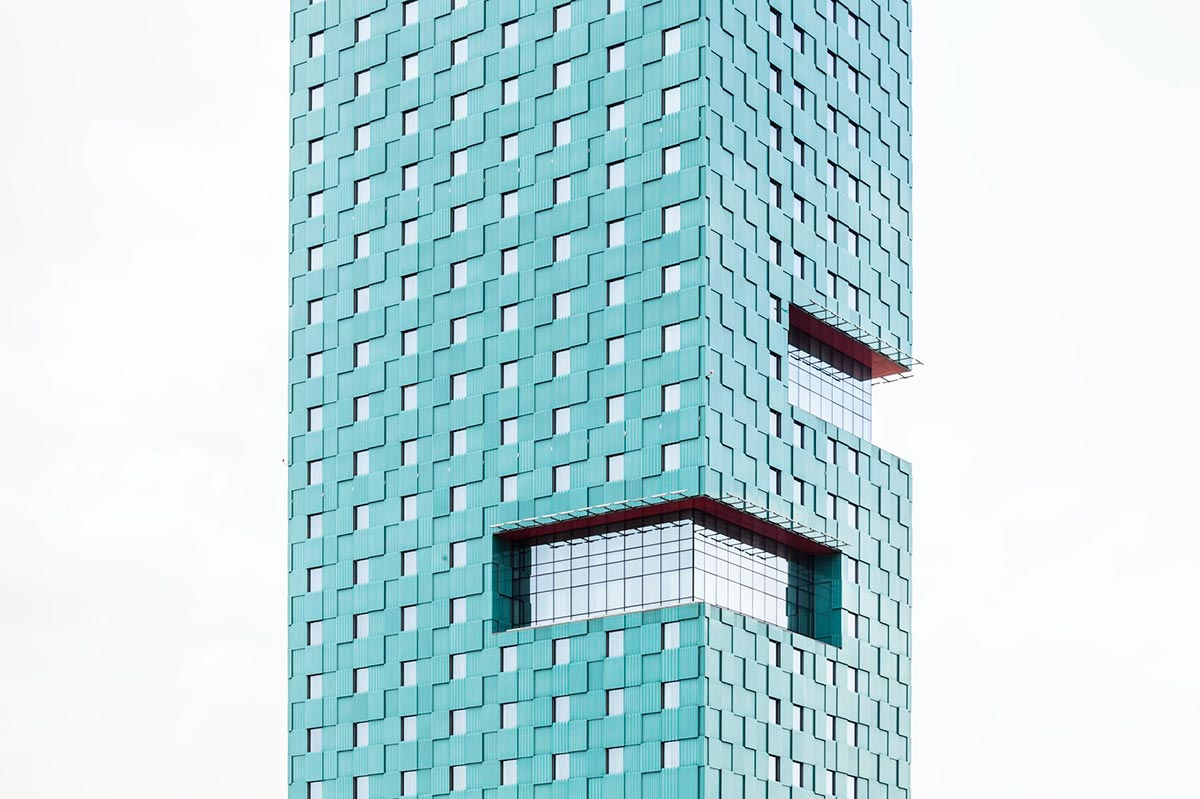

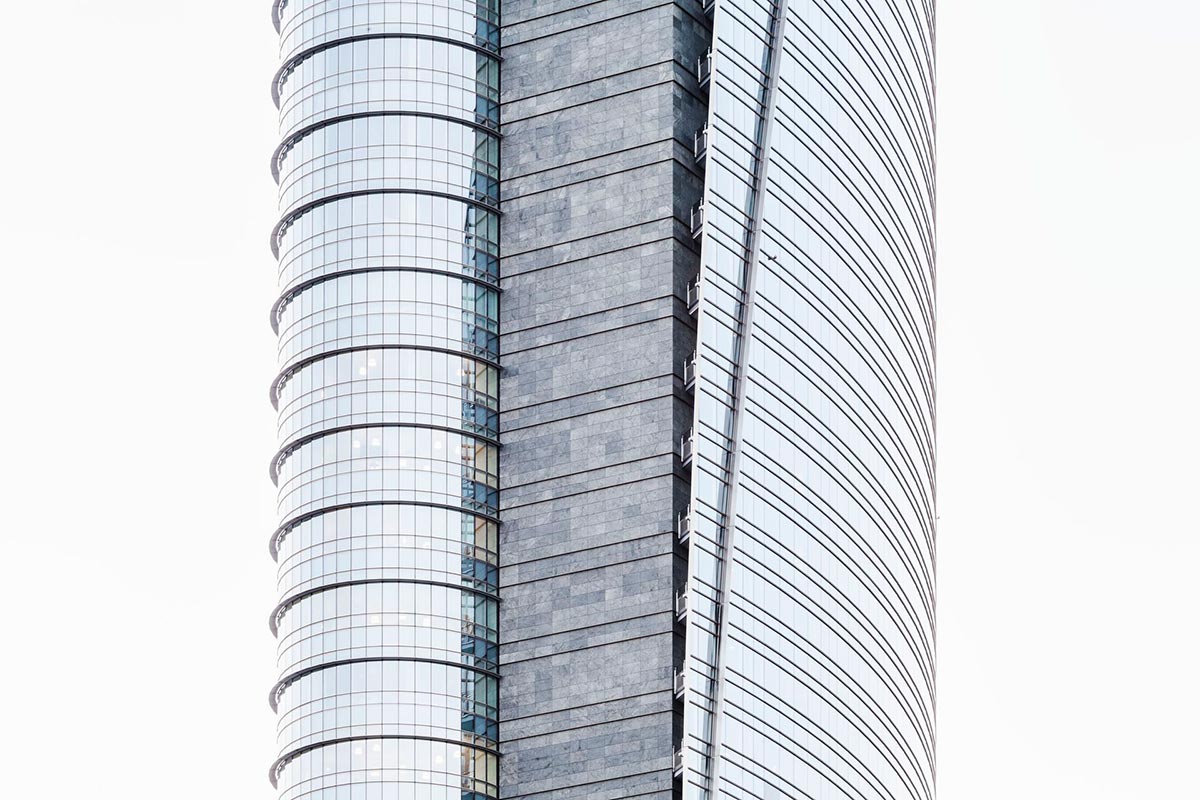

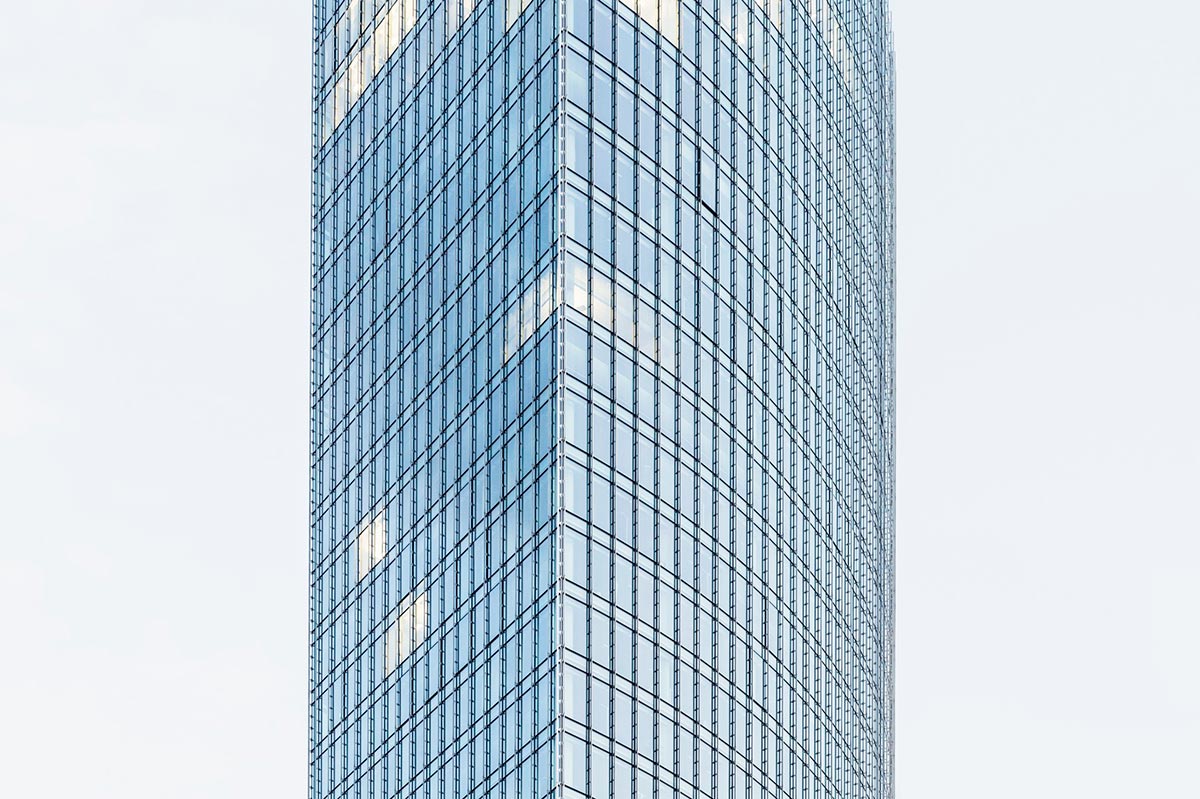

Architectural landscapes.

Lorenzo Piovella is the Milan-based artist. He is specialized in research about stereotypes relating to man-modified landscapes: the skyscrapers in his pictures look the sci-fi spaceships and even the natural scenery feels a quiet unreal. We have asked Lorenzo a few questions about his work and life and how it’s all connected to the buildings.

Are you working on any project right now?

At the moment I’m working on After New Topographics: Photographs of a Digitally-Altered Landscape. I began developing this project with the aim of synthesizing the different elements that have characterised my artistic research over the last years. It’s an operation that acts as an imagery collector; it is a sort of archive in which a multitude of suggestions related to artificial landscapes merges together.

The title is a clear reference to the famous exhibition held at George Eastman House in Rochester in 1975, curated by William Jenkins and entitled New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape. I don’t think we need to talk about it, we well know what the consequences have been: on the one side eight American photographers including Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz and Stephen Shore, spokesmen of a way to describe the U.S. environment which continues to exist; on the other side the German Bernd and Hilla Becher, founders of the “Dusseldorf School” who gave birth to authors like Gursky, Ruff, Struth and Hofer who revolutionised the way to conceive contemporary photography. After New Topographics developed into a hybrid dimension where the arid atmosphere typical of the South-western United States merges into the fascination for the industrial infrastructures that characterise German photography.

The photo series actually embraces many more references: from the photos of the series Battleground Point, taken by Richard Misrach in an unprecedented flooded Nevada desert, to the Edward Burtynsky’s shots of Californian oil fields; passing through the rarefied artificial atmospheres of Peter Bialobrzeski’s photo series Lost in Transition, the surreal landscapes that characterize the work of Andrea Galvani and the completely digital landscapes of Orogenesis, one of the most relevant works of Joan Fontcuberta.

After New Topographics does not only draw on photography. Investigation in other media plays a crucial role too. The project has its own post-apocalyptical condition that builds up from the utter dearth that pervades a certain kind of sci-fi. The cross-references to this genre are clear: from movies like Mad Max, Waterworld and Oblivion to videogames like Fallout, Rage and Spec Ops: The Line. Despite different plots and developments they all share a common sense of vastness and emptiness.

The thing that separates the work from this kind of narration is the lack of a destructive process. We are not in front of a crumbling world that is going through some kind of catastrophe. We are faced with a universe where the time seems to be frozen. The represented structures appear spotless as if they have been never used.They’re almost like huge articles from a catalogue. This kind of temporal persistence is emphasised by the surgical use of the lighting that underlines this fake mood.

The project develops in a digital dimension through several visual references to the new aesthetic but, instead of taking inspiration from digital arts, it is inspired by the scale models represented by the shots of photographers like Thomas Demand and John Casebere. As in their works the fictitious nature of the environments is made clear, there is no attempt to hide fiction. However, it represents a useful tool to interpret the world we live in.

The project develops as a kind of collage where numerous references to the representation of man-altered landscape that have entered the collective imagination coexist. The represented landscapes are suspended in a multidimensional ecosystem to such an extent that it reveals itself through a complex mash-up of trends and phenomenology.

Did you grow up in a city or in the countryside? And what was your brightest memoir of your childhood?

I grew up in a small town playing football in the courtyards, exploring abandoned attics and riding the bike along dirty tracks through endless corn fields and yet my childhood was not always so bucolic. In fact Turate, the village where I grew up, is geographically placed in the middle of a triangle whose vertices are Milan, Como and Varese respectively.. These urban areas are spreading so much that they are merging into a micro-sprawl where the smaller villages act as a sort of residential suburbs. These micro-realities are connected to bigger urban centres through a hypertrophic web of rail and road infrastructure. Let’s imagine limitless state highways surrounded for kilometres by showrooms, factories, fast-foods, shops, petrol stations, car washes and malls: if this is not a kind of urbanity, I can’t think of any other definition for that.

My childhood was also marked by a close relationship with Milan. In fact my relatives used to live in Gratosoglio, a working -class district located in the southern area of the city. It is a sort of peninsula that is developing around Via dei Missaglia and surrounded by the countryside. It’s a place that offers a clear view of the outskirts of the city. The different building typologies that characterise Milan coexist in the same realitying. Improbable pastel colour painted flat blocks alternate with those covered by ordinary brown reflecting klinker. Here and there grows up an office building coated with mirror glasses that contribute to creating a threatening atmosphere. The whole scenery is dominated by six stately white towers designed by the architecture firm BBPR between the ‘60s and the ‘70s, maybe one of the ugliest attempt to propose a new kind of architecture.

This scenery, rich of Orwellian atmosphere, represents my first contact with the urban dimension, maybe a dystopian vision but full of charm and extremely vivid in my memory.

Which is your favourite building or landscape?

I feel attracted by any place where the human intervention has strongly modified the natural environment. There is something of extremely powerful in the way the man is trying to bend nature. It’s like a hyper evolved survival instinct that pushes mankind towards its ephemeral existence of building artefacts that become the icon of its need for immortality.

If you could do anywhere you want right now – where would you?

Right now? In a petrochemical plant.